The Yankee Doodle Movie

+ towards a theory of ultra Americana

The crisp, secluded island of Mark Mylod’s The Menu (2022) immediately felt familiar. Not the landscape, but the metaphor. The island where Ralph Fiennes’ star chef has built the ultimate farm-to-table luxury dining empire felt strangely similar to the icy Chicago of Widows (Steve McQueen, 2018) and the retrofied Atlanta of Baby Driver (Edgar Wright, 2017): a hyper-stylized world in which the characters feel less human and more like blunt, impenetrable devices. The Menu was a Yankee Doodle movie.

This is what I’ve started calling movies where a usually acclaimed, usually international director uses the United States as a fantasy landscape. In a Yankee Doodle movie, America is a flag-waving fantasia defined by gun violence, polarized classes, racial warfare, and the specter of an unattainable American dream. I’m not using the term to merely describe movies set in the United States made by anyone who wasn’t born here; Chloé Zhao’s or Andrea Arnold’s hyperrealist movies don’t qualify. The Yankee Doodle movie is awash in apple-pie-Americana, a landscape that is bullish, claustrophobic, and semi-cartoonish. These are movies that would immediately fall apart if they felt grounded in a real city or a real time with real characters, because they rely on a deliberate, heightened landscape. Essentially, the Yankee Doodle movie is the red-white-and-blue inverse of the ubiquitous yellow filter used in Hollywood to depict “exotic” foreign cities.

Widows is what first made me want a word for this term. McQueen’s Chicago is the urban oligarchy you’d find in a comic book, stuffed with the appropriate noir archetypes: the rising son of a political dynasty; the cold-blooded Heavy; a series of tragic widows, natch. In McQueen’s cool, arthouse style, the Chicago setting is less about a specific place and more about metaphor, an obvious representation of the movie’s themes of segregation and isolation. McQueen is one of my favorite directors, and even though Widows is my least favorite of his movies, it’s a perfect example of Yankee Doodledom.

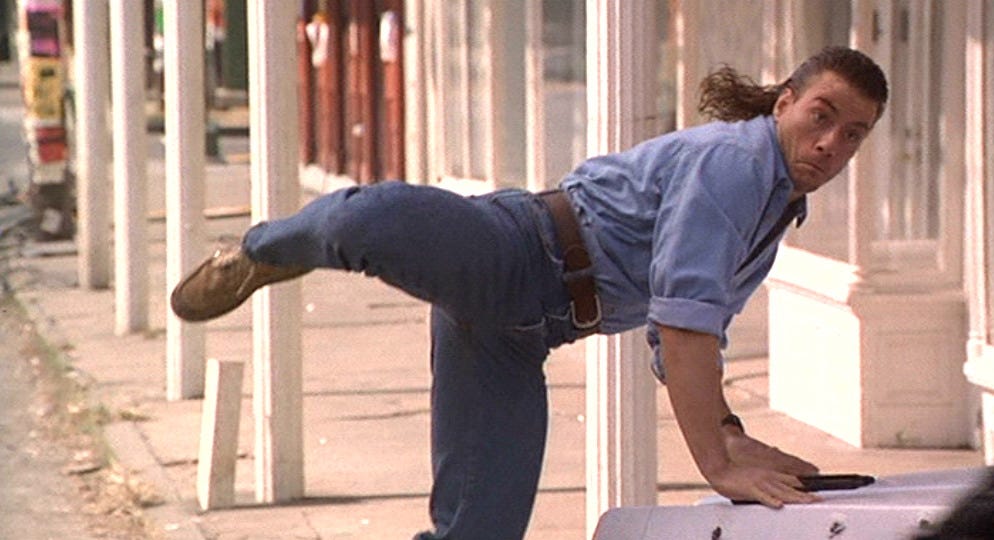

This nickname is not a slight: there are a lot of Yankee Doodle movies that I love. John Woo’s Hard Target (1993), where Jean-Claude Van Damme plays Cajun vigilante Chance Boudreaux, only works so well because of Woo’s highly stylized portrayal of New Orleans as a lawless ghosttown. Same with Stanley Tong’s Rumble in the Bronx (1995), which is set in New York (though clearly filmed in Vancouver) and was the crossover that finally brought Jackie Chan from a fantastic Hong Kong career into international action-comedy superstardom. Paul Verhoeven’s American movies, particularly RoboCop (1987) and Starship Troopers (1997), are masterpieces of self-aware Yankee Doodledom. The cities at the center of the Yankee Doodle movie are like Epcot approximations, they bear enough of a resemblance to be familiar but are still elastic enough for cartoonish satire.

In a good Yankee Doodle movie, I see the filmmaker poking a hole through the fabric of Americana, testing the sturdiness of the America of Hollywood film. In The Menu, the exclusive restaurant is the product of rampant capitalist greed, propped up by a star-obsessed media culture and funded by corrupt investors. In Hard Target, the cost of living, lack of support for veterans, and useless police force have created an underclass of desperate and vulnerable men ripe for predation by a group of depraved elites. These movies dramatize American individualism, capitalism, and greed to a savage and ridiculous end that, in their fantastical universe, is the only possible conclusion.

An unsuccessful Yankee Doodle movie would be something like The Mustang (Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, 2019), a straightforward and miserable redemption story about western masculinity. Matthias Schoenaerts is completely unbelievable as an incarcerated man named, for some reason, “Roman Coleman.” Alongside Roman is a cheery magical Negro who loves to help out Roman before he, predictably, dies. The Mustang replicates the tired, racist clichés typical of a Hollywood western without questioning them. It’s a superficial collection of a well-replicated Americana rather than an investigation into what these tropes actually mean.

I’m still refining the Yankee Doodle theory but it’s not to question a movie’s supposed authenticity. I just want to examine how directors use setting. Unlike Sam Elliott, a 20th century Sacramentan who seems to think he is an actual cowboy, I’m not interested in becoming the Americana cop. Non-Americans deconstructing Americana is a foundation of Hollywood moviemaking. Look at the Spaghetti Western, where Italian filmmakers grafted American ideas of manifest destiny onto Japanese samurai stories, or the German Expressionist filmmakers who were responsible for the creature feature, horror, and film noir genres. Getting into knots about the un-American and the immigrant is some revisionist Bari Weiss, McCarthyist shit. America has long exported fanciful ideas about itself to the world; the Yankee Doodle movie is the response.

While I wrestle with how Yankee Doodle movies fit into the long history of film treating American audiences as the default, I see in them a potential reckoning with Hollywood’s construction of America—and with American filmmaking’s history as a geopolitical force. These movies fascinate me because they reverse the traditional Hollywood gaze that flattens foreign landscapes. They do to us what we have done, for a century of filmmaking, to others.

The self-conscious creation of America in these movies offers an opportunity to explore the artificiality and contradictions of Americana; whether directors take that opportunity is a different question. The Yankee Doodle movie highlights how America is perceived by those who have lived outside of it: a country that is both wasteland and playground. It’s a portrait of us from a broader perspective, one that is not always flattering but that is often, troublingly, perceptive.